SINGAPORE — Every day Mr Wesley Seah looks through magnified copies of a Chinese calligraphy reference book on his laptop before painstakingly practising his brush strokes.

The 49-year-old then gets his mum or friends to tell him whether he is writing the characters correctly.

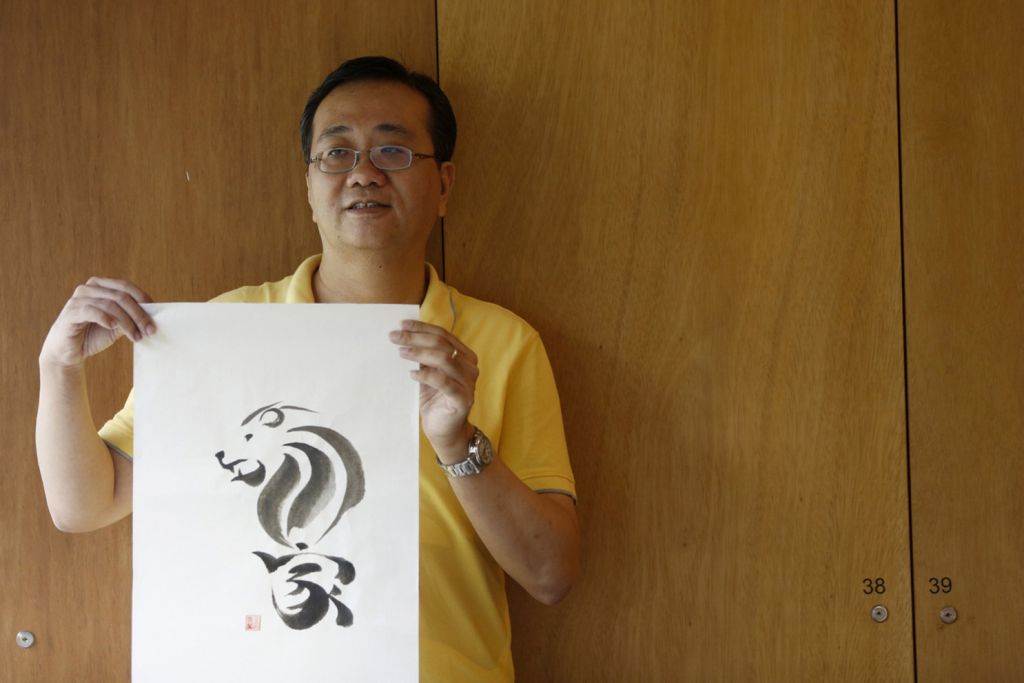

Mr Seah is completely blind in his right eye and partially sighted in his left but he has not let his disability stop him from pursuing his passion for Chinese calligraphy and painting.

To support his aspirations to improve his art, the TODAY Enable Fund has given him S$2,000, which he intends to spend on Chinese ink painting courses at LaSalle College of the Arts.

Mr Seah is one of nine beneficiaries receiving help from the TODAY Enable Fund set up last December to support efforts aimed at enhancing the education, skills and employment prospects of people with disabilities.

Once a high-flying banking consultant he started his own headhunting business. But in 2002, at the age of 34, Mr Seah was diagnosed with advanced stage glaucoma — an eye condition that typically affects older people.

His vision continued to deteriorate over the next seven years to the point of zero vision in his right eye and only 30 to 50 per cent of vision left in his left eye. The exact cause of his condition remains a mystery but instead of dwelling on his misfortune Mr Seah adopted a positive attitude.

“Why would I want to keep brooding over things?” he said. “My visual impairment could be a signal that I should … spend more time in Singapore with my parents, and be more grounded.”

For the last seven years, he has been working as a coordinator and project guide at Dialogue in the Dark (DiD) Singapore, a teaching and learning facility which gives visitors a taste of life as a blind person with the aim of raising awareness of marginalised communities.

His interest in painting was piqued after his DiD boss introduced him and his colleagues to a Chinese brush painting course — led by social artist Ms Chi Pin Lay — in early 2015.

Today painting has become an avenue for him to express his emotions.

“Each of the strokes tells a lot of stories,” he said. “When (I’m) angry … people can tell that I’m venting my anger onto the brush and paper based on the way I perform my strokes. When (I’m) in a good mood, (my) strokes will be very gentle and tender.”

He explained that although people may think that a visually-impaired person cannot paint, it can be done — just in a different way.

For instance, to create different shades of grey — which he is unable to discern — he varies the amount of water he adds to different palettes of black ink and lines them up in a row, committing their positions to memory.

He hopes to hold his own exhibition to raise funds for the needy, adding: “I think it is good to turn my disability into strength.”